In this post I will show you how to break down Linux system load by the load contributor or reason. You can drill down into the “linux system load in thousands” and “high system load, but low CPU utilization” problem patterns too.

- Introduction - terminology

- Troubleshooting high system load on Linux

- Drilling down deeper - WCHAN

- Drilling down deeper - kernel stack

- How to troubleshoot past problems

- Summary

- Further reading

Introduction - Terminology

- The system load metric aims to represent the system “resource demand” as just a single number. On classic Unixes, it only counts the demand for CPU (threads in Runnable state)

- The unit of system load metric is “number of processes/threads” (or tasks as the scheduling unit is called on Linux). The load average is an average number of threads over a time period (last 1,5,15 mins) that “compete for CPU” on classic unixes or “either compete for CPU or wait in an uninterruptible sleep state” on Linux

- Runnable state means “not blocked by anything”, ready to run on CPU. The thread is either currently running on CPU or waiting in the CPU runqueue for the OS scheduler to put it onto CPU

- On Linux, the system load includes threads both in Runnable (R) and in Uninterruptible sleep (D) states (typically disk I/O, but not always)

So, on Linux, an absurdly high load figure can be caused by having lots of threads in Uninterruptible sleep (D) state, in addition to CPU demand.

Troubleshooting high system load on Linux

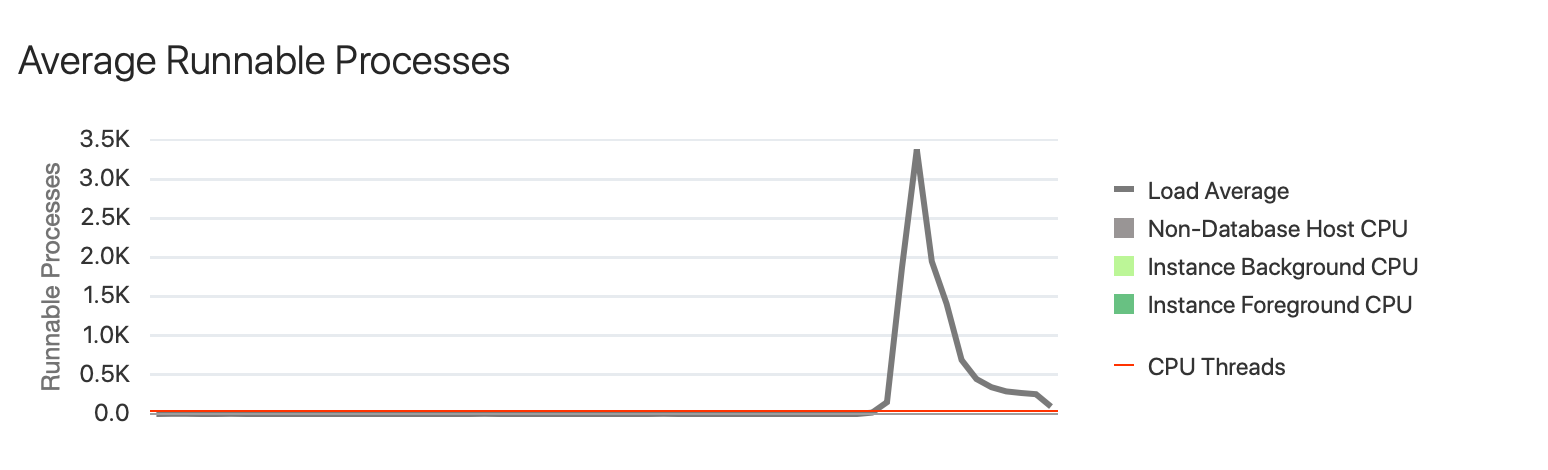

Here’s one example from a Linux database server with 32 CPUs:

The system load, incorrectly labeled as “runnable processes” by the above monitoring tool, jumped to over 3000!

The system load, incorrectly labeled as “runnable processes” by the above monitoring tool, jumped to over 3000!

Let’s confirm this with standard OS level commands, to avoid getting misled by potential GUI magic by the monitoring tool:

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ w 11:49:29 up 13 days, 13:55, 2 users, load average: 3446.04, 1242.09, 450.47 USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT tanel pts/0 192.168.0.159 Thu14 21:09m 0.05s 0.05s -bash tanel pts/1 192.168.0.159 11:46 1.00s 0.36s 0.23s w

Does this mean that we have a huge demand for CPU time? Must have lots of threads in the CPU runqueues, right?

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ sar -u 5 11:58:51 AM CPU %user %nice %system %iowait %steal %idle 11:58:56 AM all 36.64 0.00 4.42 17.17 0.00 41.77 11:59:01 AM all 41.04 0.00 3.72 26.67 0.00 28.57 11:59:06 AM all 35.38 0.00 2.95 28.39 0.00 33.27

But the CPUs are well over 50% idle! CPU utilization is around 40-45% when adding %user, %nice and %system together. %iowait means that the CPU is idle, it just happens to have a synchronous I/O submitted by a thread on it before becoming idle.

So, we don’t seem to have a CPU oversubscription scenario in this case. Is there a way to systematically drill down deeper by measuring what (and who) is contributing to this load then?

Yes, and it’s super simple. Remember, the current system load is just the number of threads (called tasks) on Linux that are either in R or D state. We can just run ps to list the current number of threads in these states:

Update: You should use

ps -eLo(with capital L) to list all threads, not only proccesses (thread groups). I previously had usedps -eoin my example, as I knew my workload was just a bunch of single-threaded (Oracle) processes and each Linux kernel thread gets shown as a separate process/thread group with justps -eo. But the correct and complete approach is to useps -eLo, to avoid accidentally missing busy threads in multithreaded processes that you inevitably have.

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ ps -eLo s,user | grep ^[RD] | sort | uniq -c | sort -nbr | head -20

3045 D root

20 R oracle

3 R root

1 R tanel

In the command above, ps -eo s,user will list the thread state field first and any other fields of interest (like username), later. The grep ^[RD] filters out any threads in various “idle” and “sleeping” states that don’t contribute to Linux load (S,T,t,Z,I etc).

Indeed, in addition to total 24 threads in Runnable state (R), it looks like there’s over 3000 threads in Uninterruptible Sleep (D) state that typically (but not always) indicates sleeping due to synchronous disk IO. They are all owned by root. Is there some daemon that has gone crazy and has all these active processes/threads trying to do IO?

Let’s add one more column to ps to list the command line/program name too:

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ ps -eLo s,user,cmd | grep ^[RD] | sort | uniq -c | sort -nbr | head -20

15 R oracle oracleLIN19C (LOCAL=NO)

3 D oracle oracleLIN19C (LOCAL=NO)

1 R tanel ps -eo s,user,cmd

1 R root xcapture -o /backup/tanel/0xtools/xcaplog -c exe,cmdline,kstack

1 D root [kworker/6:99]

1 D root [kworker/6:98]

1 D root [kworker/6:97]

1 D root [kworker/6:96]

1 D root [kworker/6:95]

1 D root [kworker/6:94]

1 D root [kworker/6:93]

1 D root [kworker/6:92]

1 D root [kworker/6:91]

1 D root [kworker/6:90]

1 D root [kworker/6:9]

1 D root [kworker/6:89]

1 D root [kworker/6:88]

1 D root [kworker/6:87]

1 D root [kworker/6:86]

1 D root [kworker/6:85]

But now “root” seems to be gone from the top and we see only some Oracle processes near the top, with relatively little R/D activity. My command has a head -20 filter in the end to avoid printing out thousands of lines of output when most of the ps output lines are unique, that is the case here with all the individual kworker threads with unique names. There are thousands of them, each contributing just “1 thread with this name” to the load summary.

If you don’t want to start mucking around with further awk/sed commands to group the ps output better, you can use my pSnapper from 0x.tools that does the work for you. Also, it samples thread states multiple times and prints a breakdown of activity averages (to avoid getting misled by a single “unlucky” sample):

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ psn

Linux Process Snapper v0.18 by Tanel Poder [https://0x.tools]

Sampling /proc/stat for 5 seconds... finished.

=== Active Threads ================================================

samples | avg_threads | comm | state

-------------------------------------------------------------------

10628 | 3542.67 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible)

37 | 12.33 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU)

17 | 5.67 | (oracle_*_l) | Disk (Uninterruptible)

2 | 0.67 | (xcapture) | Running (ON CPU)

1 | 0.33 | (ora_lg*_xe) | Disk (Uninterruptible)

1 | 0.33 | (ora_lgwr_lin*) | Disk (Uninterruptible)

1 | 0.33 | (ora_lgwr_lin*c) | Disk (Uninterruptible)

samples: 3 (expected: 100)

total processes: 10470, threads: 11530

runtime: 6.13, measure time: 6.03

By default, pSnapper replaces any digits in the task’s comm field before aggregating (the comm2 field would leave them intact). Now it’s easy to see that our extreme system load spike was caused by a large number of kworker kernel threads (with “root” as process owner). So this is not about some userland daemon running under root, but a kernel problem.

Drilling down deeper - WCHAN

I’ll drill down deeper into this with another instance of the same problem (on the same machine). System load is in hundreds this time:

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ w 13:47:03 up 7 days, 15:53, 3 users, load average: 496.62, 698.40, 440.26 USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT tanel pts/0 192.168.0.159 13:36 7:03 0.06s 0.06s -bash tanel pts/1 192.168.0.159 13:41 7.00s 0.32s 0.23s w tanel pts/2 192.168.0.159 13:42 3:03 0.23s 0.02s sshd: tanel [priv]

Let’s break the demand down by comm and state fields again, but I’ll also add the current system call and kernel wait location (wchan) to the breakdown. With these extra fields, I should run pSnapper with sudo as modern Linux kernel versions tend to block access to (or hide values in) some fields, when running as non-root:

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ sudo psn -G syscall,wchan

Linux Process Snapper v0.18 by Tanel Poder [https://0x.tools]

Sampling /proc/syscall, stat, wchan for 5 seconds... finished.

=== Active Threads ==========================================================================================

samples | avg_threads | comm | state | syscall | wchan

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

511 | 255.50 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | blkdev_issue_flush

506 | 253.00 | (oracle_*_l) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | do_blockdev_direct_IO

28 | 14.00 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0

1 | 0.50 | (collectl) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0

1 | 0.50 | (mysqld) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0

1 | 0.50 | (ora_lgwr_lin*c) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | io_submit | inode_dio_wait

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_l) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | 0

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | SYSC_semtimedop

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | read_events

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | read | 0

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | semtimedop | SYSC_semtimedop

You may need to scroll right to see the full output.

In the above breakdown of current system load, close to half of activity was caused by kernel kworker threads that were currently sleeping in blkdev_issue_flush kernel function responsible for an internal fsync to ensure that the writes get persisted to storage. The remaining “close to half” active threads were by oracle processes, waiting in a synchronous pread64 system call, in do_blockdev_direct_IO kernel function.

From the “Running (ON CPU)” lines you see that there was some CPU usage too, but doesn’t seem to be anywhere near to the hundreds of threads in I/O sleeps.

While doing these tests, I ran an Oracle benchmark with 1000 concurrent connections (that were sometimes idle), so the 253 sessions waiting in the synchronous pread64 system calls can be easily explained. Synchronous single block reads are done for index tree walking & index-based table block access, for example. But why do we see so many kworker kernel threads waiting for I/O too?

The answer is asynchronous I/O and I/Os done against higher level block devices (like the device-mapper dm devices for LVM and md devices for software RAID). With asynchronous I/O, the thread completing an I/O request in kernel memory structures is different from the (application) thread submitting the I/O. That’s where the kernel kworker threads come in and the story gets more complex with LVMs/dm/md devices (as there are multiple layers of I/O queues on the request path).

So you could say that the 253 thread where the oracle processes were sleeping within the pread64 syscall were the synchronous reads and the 255.5 kernel threads (without a system call as kernel code doesn’t need system calls to enter kernel mode) are due to asynchronous I/O.

Note that while synchronous I/O waits like

pread64will contribute to Linux system load because they end up in D state, the asynchronous I/O completion check (and IO reaping) system callio_geteventsends up in S state (Sleeping), if it’s instructed to wait by the application. So, only synchronous I/O operations (by the application or kernel threads) contribute to Linux system load!Additionally, the

io_submitsystem call for asynchronous submission of I/O requests may itself get blocked before a successful IO submit. This can happen if the I/O queue is already full of non-complete, non-reaped I/O requests or there’s a “roadblock” somewhere earlier on the path to the block device (like a filesystem layer or LVM issue). In such case anio_submitcall itself would get stuck (despite the supposed asynchronous nature of I/O) and the thread issuing the I/O ends up waiting in D state, despite the I/O not having even been sent out to the hardware device yet.

There’s at least one Linux kernel bug causing trouble in the touchpoint of kworkers and dm/md devices in high-throughput systems, but I’ll leave it to a next post.

You don’t have to guess where the bottleneck resides, just dig deeper using what pSnapper offers. One typical question is that which file(s) or devices are we waiting for the most? Let’s add filename (or filenamesum that consolidates filenames with digits in them into one) into the breakdown:

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ sudo psn -G syscall,filenamesum

Linux Process Snapper v0.18 by Tanel Poder [https://0x.tools]

Sampling /proc/syscall, stat for 5 seconds... finished.

=== Active Threads =======================================================================================================

samples | avg_threads | comm | state | syscall | filenamesum

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2027 | 506.75 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] |

1963 | 490.75 | (oracle_*_l) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | /data/oracle/LIN*C/soe_bigfile.dbf

87 | 21.75 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] |

13 | 3.25 | (kworker/*:*) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] |

4 | 1.00 | (oracle_*_l) | Running (ON CPU) | read | socket:[*]

2 | 0.50 | (collectl) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] |

1 | 0.25 | (java) | Running (ON CPU) | futex |

1 | 0.25 | (ora_ckpt_xe) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | /data/oracle/XE/control*.ctl

1 | 0.25 | (ora_m*_linprd) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] |

1 | 0.25 | (ora_m*_lintes) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] |

Apparently the system load has increased by now (we have over 1000 active threads in R/D state). Most of the synchronous read waits witnessed are against /data/oracle/LIN*C/soe_bigfile.dbf file (by oracle user). The kworker threads don’t show any filenames for their I/Os as pSnapper gets the filename from the system call arguments (and resolves the file descriptor to a filename, where possible) — but kernel threads don’t need system calls as they are already operating deep in the kernel, always in kernel mode. Nevertheless, this field is useful in many application troubleshooting scenarios.

Drilling down deeper - kernel stack

Let’s dig even deeper. You’ll need to scroll right to see the full picture, I’ve highlighted some things in all the way to the right. We can sample the kernel stack of a thread too (kernel threads and also userspace application threads, when they happen to be executing kernel code):

[tanel@linux01 ~]$ sudo psn -p -G syscall,wchan,kstack

Linux Process Snapper v0.18 by Tanel Poder [https://0x.tools]

Sampling /proc/wchan, stack, syscall, stat for 5 seconds... finished.

=== Active Threads =======================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================================

samples | avg_threads | comm | state | syscall | wchan | kstack

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

281 | 140.50 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | blkdev_issue_flush | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->generic_write_sync()->xfs_file_fsync()->xfs_blkdev_issue_flush()->blkdev_issue_flush()

211 | 105.50 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | call_rwsem_down_read_failed | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->generic_write_sync()->xfs_file_fsync()->xfs_ilock()->call_rwsem_down_read_failed()

169 | 84.50 | (oracle_*_li) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | call_rwsem_down_write_failed | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_pread64()->vfs_read()->do_sync_read()->xfs_file_aio_read()->xfs_file_dio_aio_read()->touch_atime()->update_time()->xfs_vn_update_time()->xfs_ilock()->call_rwsem_down_write_failed()

64 | 32.00 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | xfs_log_force_lsn | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->generic_write_sync()->xfs_file_fsync()->xfs_log_force_lsn()

24 | 12.00 | (oracle_*_li) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | call_rwsem_down_read_failed | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_pread64()->vfs_read()->do_sync_read()->xfs_file_aio_read()->xfs_file_dio_aio_read()->__blockdev_direct_IO()->do_blockdev_direct_IO()->xfs_get_blocks_direct()->__xfs_get_blocks()->xfs_ilock_data_map_shared()->xfs_ilock()->call_rwsem_down_read_failed()

5 | 2.50 | (oracle_*_li) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | pread64 | do_blockdev_direct_IO | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_pread64()->vfs_read()->do_sync_read()->xfs_file_aio_read()->xfs_file_dio_aio_read()->__blockdev_direct_IO()->do_blockdev_direct_IO()

3 | 1.50 | (oracle_*_li) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0 | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_pread64()->vfs_read()->do_sync_read()->xfs_file_aio_read()->xfs_file_dio_aio_read()->__blockdev_direct_IO()->do_blockdev_direct_IO()

2 | 1.00 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | call_rwsem_down_write_failed | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->xfs_end_io_direct_write()->xfs_iomap_write_unwritten()->xfs_ilock()->call_rwsem_down_write_failed()

2 | 1.00 | (kworker/*:*) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0 | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->generic_write_sync()->xfs_file_fsync()->xfs_blkdev_issue_flush()->blkdev_issue_flush()

2 | 1.00 | (oracle_*_li) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | io_submit | call_rwsem_down_write_failed | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_io_submit()->do_io_submit()->xfs_file_aio_read()->xfs_file_dio_aio_read()->touch_atime()->update_time()->xfs_vn_update_time()->xfs_ilock()->call_rwsem_down_write_failed()

1 | 0.50 | (java) | Running (ON CPU) | futex | futex_wait_queue_me | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_futex()->do_futex()->futex_wait()->futex_wait_queue_me()

1 | 0.50 | (ksoftirqd/*) | Running (ON CPU) | [running] | 0 | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->smpboot_thread_fn()

1 | 0.50 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | worker_thread | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()

1 | 0.50 | (kworker/*:*) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [kernel_thread] | worker_thread | ret_from_fork_nospec_begin()->kthread()->worker_thread()->process_one_work()->dio_aio_complete_work()->dio_complete()->generic_write_sync()->xfs_file_fsync()->xfs_blkdev_issue_flush()->blkdev_issue_flush()

1 | 0.50 | (ora_lg*_xe) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | io_submit | inode_dio_wait | system_call_fastpath()->SyS_io_submit()->do_io_submit()->xfs_file_aio_write()->xfs_file_dio_aio_write()->inode_dio_wait()

1 | 0.50 | (oracle_*_li) | Disk (Uninterruptible) | [running] | 0 | -

Looks like a different hiccup has happened in my benchmark system now, additional WCHAN (kernel sleep location) values have popped up in the report: call_rwsem_down_*_failed by both Oracle and kworker threads and xfs_log_force_lsn waits by 32 kworker threads. rwsem stands for “reader-writer semaphore” that is essentially a low level lock. So, a large part of our system load (D state waits) are caused by some sort of locking in the kernel now and not by waiting for hardware I/O completion.

If you scroll all the way right and follow the kernel function call chain, it becomes (somewhat) evident that we are waiting for XFS inode locks when accessing (both reading and writing) files. Additionally, when searching what the xfs_log_force_lsn function does, you’d see that this is an XFS journal write that persists XFS metadata updates to disk so that you wouldn’t end up with a broken filesystem in case of a crash. XFS delayed logging must be ordered and checkpoints atomic, so there may be cases where one XFS-related kworker on one CPU will block other kworkers (that have assumed the same role) on remaining CPUs. For example, if the XFS log/checkpoint write is too slow for some reason. It’s probably not a coincidence that pSnapper shows exactly 32 threads waiting in xfs_log_force_lsn function on my 32 CPU system.

Why do we even have noticeable XFS metadata generation? Unlike ZFS, XFS does not log actual data in the journal, just the changed file metadata. Every time you write to a file, some metadata must be logged (last file modification timestamp) and even reads can cause metadata to be generated (filesystem mount options noatime and to lesser extent relatime avoid metadata generation on reads).

So in addition to the 32 kernel threads waiting for XFS log sync completion, we have hundreds of concurrent application processes (Oracle) and different kernel kworker threads that apparently contend for XFS inode lock (where the xfs_ilock kernel function seen in stack). All this lock contention and sleeping will contribute to system load as the threads will be in R or D state.

With any lock contention, one reasonable question is “why hasn’t the lock holder released it yet?”, in other words, what is the lock holder itself doing for so long? This could be explained by slow I/O into the XFS filesystem journal, where the slow XFS log sync prevents everyone else from generating more XFS metadata (buffers are full), including the thread that may already hold an inode lock of the “hot” file because it wants to change its last change timestamp. And everyone else will wait!

So, the top symptom will point towards an inode lock contention/semaphore problem, while a deeper analysis will show that slow XFS journal writes, possibly experienced just by one thread, are the root cause. There are good performance reasons to put the filesystem journal to a separate block device even in the days of fast SSDs. I have just connected a few dots here thanks to previously troubleshooting such problems, but in order to be completely sytematic, kernel tracing or xfs_stats sampling would be needed for showing the relationship with XFS log sync waits and all the inode semaphore waits. I’ll leave this to a future blog entry.

How to troubleshoot past problems?

Running ps or psn will only help you troubleshoot currently ongoing problems. If you’ve been paying attention to my Always-on Profiling of Production Systems posts, you know that I’ve published an open source super-efficient /proc sampler tool xcapture that can save a log of sampled “active thread states” into CSV files. I haven’t written fancier tools for analyzing the output yet, but on command line you can just run “SQL” against the CSV using standard Linux tools:

$ grep "^2020-11-20 11:47" 2020-11-20.11.csv | \

awk -F, '{ printf("%-2s %-10s %-15s %s\n", $5, $4, $7, $8) }' | \

sort | uniq -c | sort -nbr

32165 D root [no_syscall] blkdev_issue_flush

5933 D oracle pread64 do_blockdev_direct_IO

1001 R oracle [running] 0

20 R root [running] 0

16 R oracle futex futex_wait_queue_me

12 D oracle [running] 0

8 R oracle read sk_wait_data

5 D oracle io_submit inode_dio_wait

4 R oracle pread64 do_blockdev_direct_IO

2 R tanel [running] 0

2 R oracle semtimedop SYSC_semtimedop

2 D root [running] 0

2 D root [no_syscall] msleep

1 R root [running] worker_thread

1 R oracle [running] do_blockdev_direct_IO

1 R oracle nanosleep hrtimer_nanosleep

1 R oracle io_getevents read_events

1 D root [no_syscall] xfs_log_force

1 D root [no_syscall] worker_thread

1 D root [no_syscall] hub_event

1 D oracle [running] read_events

1 D oracle pwrite64 wait_on_page_bit

1 D oracle pwrite64 blkdev_issue_flush

1 D oracle io_getevents read_events

In the above example, I just zoomed in to one minute of time of interest (11:47) with grep and then just used awk, sort and uniq for projecting fields of interest and a group by + order by top activity. Note that I didn’t have 32165 threads active here, I’d need to divide this figure with 60 as I’m zooming in to a whole minute (sampling happens once per second) to get the average active threads in R/D states.

Summary

The main point of this article was to demonstrate that high system load on Linux doesn’t come only from CPU demand, but also from disk I/O demand — and more specifically number of threads that end up in the uninterruptible sleep state D for whatever reason. Sometimes this reason is synchronous disk I/O, but sometimes the threads don’t even get that far when they hit some kernel-level bottleneck even before getting to submit the block I/O to the hardware device. Luckily with tools like pSnapper (or just ps with the right arguments), it is possible to drill down pretty deep from userspace, without having to resort to kernel tracing.

Further Reading

Brendan Gregg did some archaeological investigation into the origins of Linux load accounting differences. In short, the developer felt that it wouldn’t be right for the system load to drop, in case there’s an I/O bottleneck due to things like swapping. When you hit a sudden I/O bottleneck, then CPU utilization typically drops as your code waits more and it felt unreasonable to the developer that the “system load” drops lower while the system gets less work done. In other words, on Linux the load metric tries to account system load, not just CPU load only. However, as I’ve shown above, there are quite a few reasons (like asynch I/O activity not contributing to load) why the single-number system load metric alone won’t tell you the complete picture of your actual system load.

Discussion

The latest HackerNews discussion is here

Next articles

Here’s a list of blog entries that I think of writing next (I’ll update these with links once done):

- Application I/O waits much longer than block I/O latency in iostat?

- Troubleshooting too many (thousands of) kworker threads

- Pressure Stall Information (PSI) as the new Linux load metric, how useful is it?